What Makes Star Trek Special?

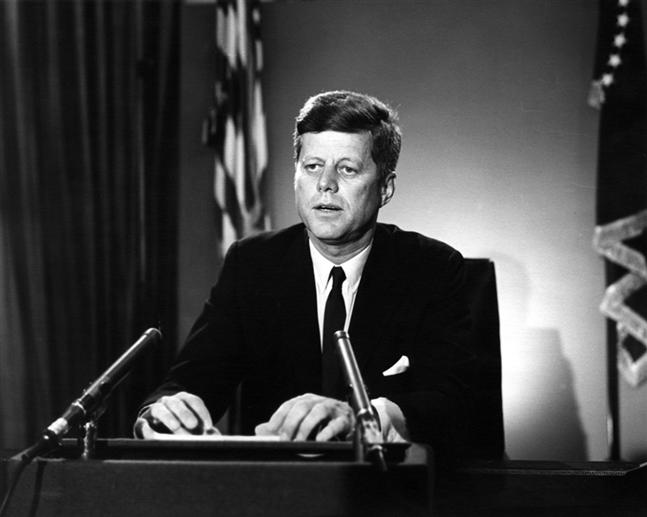

In October of 1962, my mother was thirteen years old. One evening, she was watching the news on TV with her parents and her two brothers when President Kennedy came on to address the nation. He said that the US had discovered that the Soviet Union was deploying ballistic missiles to Cuba, close enough to American soil that they could easily target most of the continental US. Kennedy said that any such missile launched from Cuba would be seen as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States and would trigger full retaliation.

This was when the public became aware of what we now call the Cuban Missile Crisis. It only lasted a few weeks, but it was one of the scariest periods of the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union, nearly resulting in a nuclear exchange multiple times. To us, this is history, and we know that despite the close calls civilization survived this era more or less intact, but that was far from guaranteed at the time. Certainly to my young mother watching these events unfold as she tried to live her life as a normal teenager, it seemed that the world was about to plunge into full-on nuclear war, and she might never have a chance to grow up.

In September 1966, four more years into the Cold War, the National Broadcasting Company aired the first episode of a new show called Star Trek. It was the first American science fiction series with a regular cast that was aimed at adults. Like a lot of sci-fi, it used its futuristic setting to indirectly explore and comment on real-world issues, but where a lot of sci-fi did so via cautionary tales examining how things can go wrong and what dark places that might take us, Star Trek did so via aspirational tales, examining how things could go right and what a bright future might look like. At a time when it was difficult to be optimistic and it seemed like humanity was about to destroy itself over nationalistic squabbles, Star Trek showed a vision where not only had humanity survived, but it had come together to explore the stars.

On the surface, it was an adventure show with each episode featuring an exiting and suspenseful plot peppered with cool gadgets and starship battles telling a satisfying story of Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock triumphing over evil. But every story was set in a vision of what the world might look like if humanity got itself together. That vision was a constant undercurrent baked into the premise and setting.

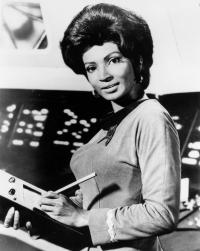

Take a look at the composition of the main cast. Today, it might seem pretty male and pretty white. But at the time, it was the most racially diverse live action series on American television. It was unprecedented to feature an Asian man and an African woman as competent and intelligent professionals on equal footing with their white male colleagues. But in Star Trek’s imagined future, all these characters are working together as respected officers, and it’s no big deal.

Lieutenant Sulu was played by George Takei, who as a child was one of over 125,000 Japanese Americans who were taken from their homes and forced to live in internment camps for almost four years during World War II, supposedly as a security measure since Japan was an enemy nation at the time. Twenty years later, when Takei wanted to drop out of architecture school to become an actor, his father warned him that positive portrayals of Asians in American theater and media were hard to come by. As Takei describes it:

My father wanted me to be an architect. I was an architecture student at UC Berkeley. I lasted two years, but my real passion was acting. My father said: “Look at television, look at the movies, look at Broadway. Those roles for Asians are terrible; all the stereotypes. Is that what you want to be?” I took that as a challenge to prove him wrong.

Takei did struggle for a few years, but then he was cast in Star Trek. Again, in Takei’s words:

The show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, told me the idea was a metaphor for the fact that the earth’s strength lay in its diversity; people from all over the world, working out their problems and being a team – and boldly going where no one had gone before.

Lieutenant Uhura was played by Nichelle Nichols. At a banquet held by the NAACP, Nichols met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who told her that Star Trek was the only show his children were allowed to watch, specifically because of the positive, humanizing portrayal of Uhura at a time when black women on American television were almost always playing servants. As Nichols describes it:

[T]here was Dr. Martin Luther King walking towards me with this big grin on his face. He reached out to me and said, “Yes, Ms. Nichols, I am your greatest fan.” He said that Star Trek was the only show that he, and his wife Coretta, would allow their three little children to stay up and watch. . . . [He said,] “[F]or the first time on television, we will be seen as we should be seen every day, as intelligent, quality, beautiful, people who can sing, dance, and can go to space. . .”

Astronaut Mae Jemison, the first black woman in space, cited Uhura as an inspiration, as did actor and comedian Whoopi Goldberg, who saw Star Trek as a nine-year-old girl and excitedly told her family, “I just saw a black woman on television, and she ain’t no maid!” Both of them later appeared on Star Trek: The Next Generation.

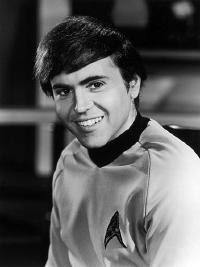

In Star Trek’s second season, a new cast member was added: Ensign Pavel Chekov. The Cold War was still in full swing, and here was Star Trek putting a Russian on the bridge. It was a statement that the war didn’t have to last forever and didn’t have to result in one side destroying the other. Humanity could find a way to get past it and become friends and allies.

By showing a future where all of these characters worked together as equals regardless of their ethnicities, genders, and origins, Star Trek quietly but unambiguously showed its audience a world that not only hadn’t blown itself up, but had set aside its differences in the pursuit of something greater, and along the way had overcome racism, sexism, and nationalism.

To be fair, the show unfortunately does have many examples of outdated views, especially sexist ones. The writers were not perfect and they faced external constraints limiting what they could do. Still, the overall intent and message are clear. Especially because the ideals depicted by the show go far beyond the backdrop of a diverse cast. The same principles of inclusion and understanding that are implied to have brought Earth together are also seen in the choices made by the show’s heroes throughout the series. I’m going to illustrate this by discussing the plot of “The Devil in the Dark”, one of the episodes of the show’s first season - so, spoiler warning for something that aired over fifty years ago.

The starship Enterprise arrives at a mining colony in response to a distress call. The colony was established on an apparently-uninhabited planet and has since become an important source of minerals for a dozen nearby worlds. But now, suddenly, miners are dying. Some kind of alien creature has shown up in the tunnels, sabotaging equipment and killing over fifty people.

Much of this episode plays out like a horror movie. Almost no one has seen the creature and lived. It’s not detectable by normal sensors or affected by normal weapons, and it apparently has the ability to quickly tunnel through solid rock. It can sneak up on miners who are alone in the tunnels with nowhere to escape and no way to defend themselves.

Our heroes Kirk and Spock figure out that the creature must be a silicon-based life form and adjust their sensors and weapons to be able to track and wound the creature. At this point, this is already a dramatic story about science overcoming a tough situation. They could kill the creature, save the mining colony, and call it a happy ending. But that’s not what happens. Instead, Kirk and Spock realize that the creature is intelligent and find a way to communicate with it. They learn that the creature, called a Horta, has only been attacking the humans to defend its own kind. The miners have unknowingly destroyed thousands of Horta eggs, since to humans they just look like rocks.

The humans were the monsters all along, due to their ignorance. But now that the Horta and the humans can understand each other, peace can be achieved. The miners will stay away from the Horta incubators and protect them from external threats, and the Horta can help the miners through the use of its incredible tunneling abilities.

This isn’t a story about a battle in which one side triumphs over the other. It’s a story where the battle is revealed to be misguided, a tragic and wasteful misunderstanding. Killing the Horta would have been a failure, not a victory, and the true victory was won by coming to an understanding, setting down weapons, and working to mutual benefit.

When speaking of this episode, the show’s creator Gene Roddenberry said, “[I]f you can learn to feel for a Horta, you may also be learning to understand and feel for other Humans of different colors, ways, and beliefs."1

Science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke said, “[I]t presented the idea, unusual in science fiction then and now, that something weird, and even dangerous, need not be malevolent. That is a lesson that many of today’s politicians have yet to learn."2

And writer Michael Chabon (who, by the way, was also the showrunner for the first season of Star Trek: Picard) said, “The episode rises above the banality of a premise as old as Grendel . . . by insisting that fear and prejudice were no match for curiosity and an open mind, that where there was consciousness there could be communication, and that even a rock, if sentient, had the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It was, in its way, a near-perfect example of what had drawn my father, and me, and fans around the world, to Star Trek and its successor shows for more than fifty years.”

This is the lesson that Star Trek teaches over and over and over again, starting in the original series and continuing to the shows still running today. Destroying your enemy, while sometimes a tragic necessity, is always a failure. True victory is when you turn an enemy into an ally.

This is the philosophy that we see the show’s heroes live up to time and again with bizarre aliens in the far reaches of the galaxy, and it’s quietly but clearly shown to be the philosophy that brought humanity together here on Earth and led them through the dark times into this bright future. The idea that true strength doesn’t come from violence or domination, but from understanding, compassion, and cooperation. The idea that if we grow past our petty differences, embrace our diversity, and work together, we can reach the stars.

Star Trek is escapist fantasy of an appealing world to live in, but it’s also a goal to shoot for and a blueprint for getting there. It’s an implicit promise that if we live up to the ideals of the United Federation of Planets, then we can actually create an equally appealing world for real.

I don’t think it’s hard to see why that kind of hope would have a lot of appeal in times of divisiveness and doubt in the future. I don’t think it’s surprising that this vision carried Star Trek from a niche show which only ran for three seasons and got canceled twice to a gigantic, global, decade-spanning phenomenon including eleven series with a growing total of over 850 episodes between them plus thirteen feature films, not to mention countless tie-in media, events, and merchandise.

The Cold War is generally considered to have come to an end in December of 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The original Star Trek was long since over, but Star Trek: The Next Generation was midway through its fifth season.

That’s what I saw on TV when I was thirteen years old, watching with my brother, father, and mother, imagining what kind of world I might grow up into.

-

The Making of Star Trek, pp. 35 & 36 ↩︎

-

Star Trek: Four Generations, pp. 8 ↩︎